Interstellar

Interstellar

Starring Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway, Jessica Chastain, Michael Caine, Casey Affleck and John Lithgow

Directed by Christopher Nolan

From Warner Bros. Pictures, Syncopy and Paramount Pictures

Rated PG-13

169 minutes

by Michael Clawson of Terminal Volume

In the great cathedral of space, no one can hear you scream, but the cosmic organs are imbued with an acoustic majesty all their own. Their thundering choruses leap and swirl to an audience of stars, supernovas, nebulas and that little speck of shivering matter we call mankind.

Christopher Nolan’s bravely beautiful Interstellar establishes humanity’s insignificance, the universe’s vastness, and how human exploration will one day narrow the margins between them. The film obliquely dabbles with religion, philosophy, science, quantum physics, and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, all under the umbrella of an adventurous space opera, emphasis on the word opera — the music is exceptional.

In the near-future, the environment is scorched to the point of collapse. Water is scarce, dust chokes out anything living, and civilization is forced to take evolutionary steps backward to hack out a meager existence in devastated farmlands. We are plopped into the dusty haze of a farm run by former NASA test pilot Cooper (Matthew McConaughey). He’s a corn farmer, because everyone is — it’s the only crop that will grow in the planet’s temperamental weather. We catch a glimpse of the dinner table: corn on the cob, corn salad, cornbread, and creamed corn. We don’t see breakfast, but my bet is on cornflakes.

After a fluctuating gravity field is discovered in his plucky daughter Murphy’s bedroom, Cooper is sent bolting into the dust and desert for answers. He ends up finding a secret NASA base intent on launching a rescue mission into deep space to discover a new world, fresh water or the answer to a world-saving proof that has stumped a mathematician played by Michael Caine. As luck would have it, the mission is short a commander. Cooper’s truck disappears into his farm’s dust at the same time the film cuts to a similar shot of a rocket blasting white smoke as it breaks free from Earth’s atmosphere. Off we go!

The first stop is to Saturn, where a quantum anomaly might turn out to be a wormhole to another uncharted area of the universe. NASA knows the anomaly leads somewhere; a dozen astronauts in a dozen different ships were sent through years earlier and three are still relaying information back. Cooper and his fellow astronauts (including Wes Bentley and Anne Hathaway) buckle up and start spiraling toward the anomaly, which is itself a gateway to the rest of the film, a gateway I will peer into but not spoil further.

Nolan has made some of the most important blockbusters of the 21st century, and he outdoes himself here with rocketships, time travel, black holes, desolate planets, twirling space stations and enough big ideas to stroke the edges of Stanley Kubrick’s all-but-untouchable 2001: A Space Odyssey. Like that picture, Interstellar is only half interested in its human characters, instead committing itself to the grander mission of human achievement, a cerebral journey into the nature of space travel and the galaxy’s dreadful expanse. It’s a theme repeated over and over again as Cooper’s tiny-by-comparison ship glides past Milky Ways, dwarf stars and rocky planetoids. In one exceptional shot — made exponentially better when rendered on IMAX’s huge screens — the ship is represented as a single pixel as it cuts across the face of Saturn. That kind of scale is not only accurate, it’s terrifying.

Nolan is an astoundingly perceptive director, but an awful cinematographer and editor. (Hoyte Van Hoytema and Lee Smith are his actual cinematographer and editor, respectively.) The editing cuts too frequently to unwanted angles or confusing perspectives; it is frustrating to see a film of this caliber struggle with the basics, and yet it does repeatedly. The cinematography is also noticeably sub-par in parts. It’s as if they didn’t get enough coverage during initial photography, and then winged it all later when the film was being edited. The rocket launch isn’t even shown until the rocket is in orbit, the spaceship is only photographed from one annoying down-the-nose GoPro-like angle, and dialogue is shot using a stale set of alternating medium shots, like this is some kind of flat Lifetime movie. I will give Nolan credit for using lots of in-camera tricks (as opposed to green screen and CGI), but the nuts and bolts of the film’s mechanical bits are wobbly and unstable. It’s a complaint that is still echoing from his Dark Knight days.

And one more gripe before switching gears: the science is little wonky. Well, a lot wonky. It renders the Theory of Relativity into a plot device with about as much nuance as an episode of Scooby Doo. The film’s big revelation — Caine’s mystical proof — is never explained enough to take it seriously. And then the plot holes: How would a planet with 2 feet of water pooled on its surface be able to sustain waves as tall as the Rocky Mountains? Doesn’t time-bending only work on things traveling the speed of light or near the speed of light? What’s the point of that Indian drone that crash lands near the cornfield? Why wouldn’t Anne Hathaway’s character have aged more after another character tinkers with a black hole? What does the proof even solve? And what’s the purpose of robots as clunky as 2001’s monolith? Remember when Neil deGrasse Tyson picked apart Gravity? With Interstellar he might have to nuke it from orbit, just to be safe.

Now that I’ve sniped at the science, let me reiterate something: Interstellar is a phenomenal movie about adventure, love, family and the reaches of the human spirit. It doesn’t portray science or space accurately because it doesn’t have to. It’s real quest is to take us into the emotional cosmos of a father separated by space and time from his daughter. The story came about after Jonathan Nolan grew interested in time travel, but not the theory as much as the scenario in which the theory is discussed. In science books, the Theory of Relativity is often framed in a diagram of a person on a train platform watching as a train, traveling the speed of light, carries another person away into the great beyond. Interstellar has two people (Murphy and Cooper), a platform (earth) and a convincing train (a rocket) and it uses that model to weave a compelling space drama that will suck you into its eternal void of deep space.

Interstellar has its Speilbergian moments, and its Kubrickian moments, and some very quintessential Nolan moments, including a scene of Cooper, gone for hours on a strange planet, asking how much real time — relatively speaking — has elapsed while he was away. “23 years,” a now-graying astronaut says. There’s also a brilliantly choreographed scene of a spaceship docking with another ship under the most extreme circumstances. The music is pumping, the camera is whirling around the ship and Cooper is fighting as hard as he can to save himself and the human race — this is Interstellar firing on all cylinders.

Scores are rarely noteworthy enough to get detailed mentions in reviews, but Hans Zimmer’s score is the rare exception. Zimmer’s electric organs, booming bass and hypnotic swells are just perfect. The music is comparable to the 1982 Philip Glass soundtrack in Godfrey Reggio’s art picture Koyaanisqatsi, itself a film about the limits of man and the unbalancing of the earth. Zimmer’s music, occasionally full of bombast and broad salvos of sound, can also quietly punctuated the dialogue, including Caine’s great recital of Dylan Thomas’ line, “Do not go gentle into that good night,” or when Cooper paws through the dry soil and ponders, “We once looked up and wondered at our place in the stars, now we just look down and worry about our place in the dirt.”

Interstellar is not without its scientific failings, but looking at what it accomplishes and what it invokes within us, it is likely to go down as one of the great science fiction movies of this generation. It has scope, it has grand ideas and it has a story large enough that it can be seen from Jupiter, which was probably the point all along.

We may be a couple of months out from the 2015 Phoenix Film Festival, but you can purchase your passes to the Festival right now at a discounted price.

We call it our Early Bird Sale, and you can take advantage of these great prices today:

We may be a couple of months out from the 2015 Phoenix Film Festival, but you can purchase your passes to the Festival right now at a discounted price.

We call it our Early Bird Sale, and you can take advantage of these great prices today:

The Overnighters

The Overnighters

Horrible Bosses 2

Horrible Bosses 2

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay — Part 1

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay — Part 1

The Theory of Everything

The Theory of Everything

Rosewater

Rosewater

Beyond the Lights

Beyond the Lights

Dumb and Dumber To

Dumb and Dumber To

Laggies

Laggies

Interstellar

Interstellar

Revenge of the Green Dragons

Revenge of the Green Dragons

Elsa & Fred

Elsa & Fred

For a horror fanatic, asking them to pick their ten favorite horror films can be a difficult challenge. So today, here are ten of my personal favorites. Enjoy!

For a horror fanatic, asking them to pick their ten favorite horror films can be a difficult challenge. So today, here are ten of my personal favorites. Enjoy!

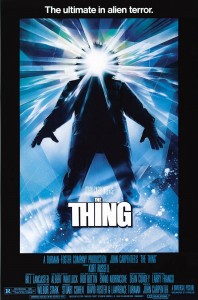

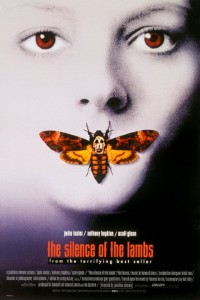

Top 10 Horror Films

Top 10 Horror Films Top 10 Horror Films

Top 10 Horror Films